The White House released a new report, “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and the Economy” last week, focusing on the economics of AI-driven automation and the recommended policy responses. This long, 55-page report follows the previous report, “Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence,” demonstrating the Administration’s commitment to AI.

The oft-neglected component of the AI-discussion is the role of policy. Lost in the heated debate between the so-called tech-elitists and the Luddites, we forget that technology by itself does not shape the economy. This White House report brings about a fresh perspective to those inundated by the alarmists’ or optimists’ point of view.

The following will summarize the report and highlight the key points. Note that the points presented here do not necessarily reflect my personal views. The summary will follow the report in the same order, so feel free to refer to the actual report to dig deeper into each section.

AI and the Macroeconomy: Technology and Productivity Growth

- Technology increases productivity, which generally also translates to an increase in average wages and living standards.

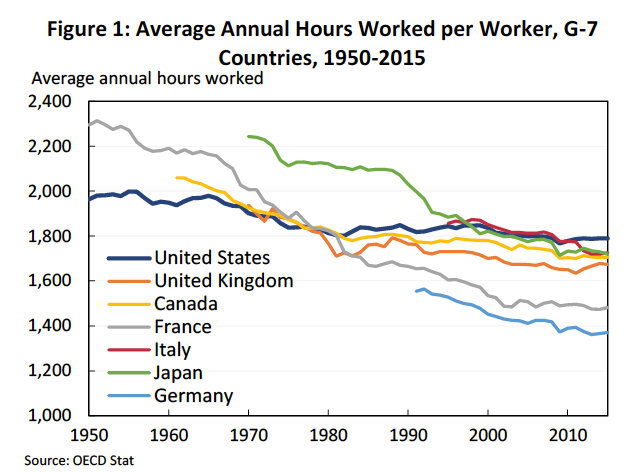

- Out of the G-7 countries, the US has uniquely seen the decline of annual hours worked per worker stop since the late 1980s (Fig 1).

- In the last decade, measured productivity growth has slowed down in 30 of the 31 advanced economies, including in the US. While a decrease in capital stock investment is also at play, the slowdown in total factor productivity growth (influenced by advances in technology), has been significant.

Historical Effects of Technical Change

- The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century is called unskill-biased technical change, where skilled crafts were replaced by automation and lower-skill labor.

- The advent of the computer in the 20th century brought about the skill-biased technical change, where routine-intensive occupations were replaced by computers and robots.

- While AI-driven automation has increased productivity, financial benefits from such innovations are not guaranteed to be broadly shared. In fact, displaced workers’ earnings recover slowly and incompletely as there appears to be a “deterioration in their ability to either to match their current skills to, or retrain for, new, in-demand jobs.”

AI and the Labor Market: The Near Term

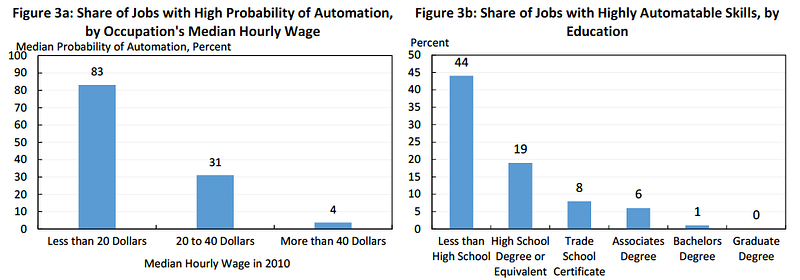

- According to the Frey and Osbourne analysis, 83% of jobs making less than $20/hr are endangered by automation, as opposed to 31% for those making $20–40, and 4% for those making above $40/hr.

- The level of education plays a huge role as 44% of those with less than a high school degree hold jobs easily displaced by AI-driven automation, whereas only 1% of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher hold such jobs.

- Humans still hold an advantage over current AI systems in occupations that require social/emotional intelligence, creativity, or high-levels of manual dexterity.

- CEA concludes that AI will fuel growth in four categories of jobs: 1) engagement with AI technologies and augmented intelligence, 2) development, especially in data mining and cleaning, 3) supervision to monitor, license, and repair AI systems, 4) response to paradigm shifts such as urban planning, AI-design, and cybersecurity.

Technology is Not Destiny — Institutions and Policies Are Critical

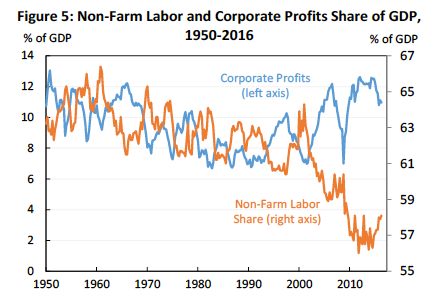

- Since the late 1970s, productivity growth has not translated to higher wages for low- and middle-income American workers. Also, starting in 2000, corporate profits as a portion of the GDP began to rise sharply, whereas non-farm labor share of the GDP started to decrease (Fig 5).

- Non-technical factors such as economic policy will shape the distribution of gains due to AI and AI-driven automation. For example, the wage premium for college-education skilled labor has continually increased over time. This creates a countervailing incentive to invest in technologies that raise the productivity of lower-skilled workers (e.g. replacing radiologists with medical imaging software and cheaper operating personnel).

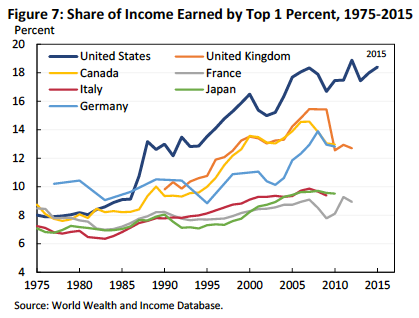

- Wages depend on collective, bargaining, minimum wage laws, and other policies that affect wage setting. In fact, US has seen higher income inequality over the last four decades, while other developed nations have seen more income parity (Fig 7).

- Other countries tend to “invest far more resources on active labor market programs that help workers navigate job transitions, such as training programs and job-search assistance.” This means that Federal policies will need to play a role to help Americans respond to changes caused by AI-driven automation.

Policy Responses

Policymakers should prepare for five primary economic effects due to AI-driven automation:

- Positive contributions to aggregate productivity growth

- Changes in the skills demanded by the job market, including greater demand for higher-level technical skills

- Uneven distribution of impact, across sectors, wage levels, education levels, job types, and locations

- Churning of the job market as some jobs disappear while others are created

- The loss of jobs for some workers in the short-run, and possibly longer depending on policy responses

Strategy #1: Invest In and Develop AI for its Many Benefits

- The government sees the opportunity to invest in research and development in AI-driven, critical areas such as health, education, energy, economic inclusion, social welfare, transportation, and the environment.

- The increasing complexity of machine learning and AI naturally leads to the opportunity to support human decision making in response to cyberattacks.

- Gender and racial diversity in the AI-specific workforce reflects the ongoing problem in the STEM field in general. Policymakers must address potential barriers from achieving diverse groups.

- Startups will play a key role in pushing innovation and incentivizing established firms to compete constantly.

Strategy #2: Educate and Train Americans for Jobs of the Future

- College- and career-ready skills in STEM areas will be critical for AI-driven markets.

- Economic barriers to education must be removed. American students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds score 15% lower on tests than higher-income peers.

- People with low levels of basic skills are at the highest risk of displacement. Access to affordable post-secondary education will be key in preparing them for good jobs.

- Likewise, the availability of high-quality job training and tools to navigate job transitions are of utmost importance.

Strategy #3: Aid Workers in the Transition and Empower Workers to Ensure Broadly Shared Growth

- In response to the rise of part-time and contingent work, policymakers will need to adapt and ensure that workers can get access to retirement, healthcare, and other benefits outside of their company.

- Currently, only a third of unemployed Americans receive insurance benefits. The report suggests up to 52 weeks of benefits to displaced workers while they prepare for job transitions or retraining.

- The President has called for improved guidance to navigate job transitions and strengthening other safety-net programs such as SNAP and TANF.

- Lastly, the report calls for raising the minimum wage, modernizing tax policy, and reducing geographic barriers to work.

New Episode

New Episode

Latest IoT News

Latest IoT News