Hannover-Messe 2019 and the Slovakian Engineer’s Joke: Industry 4.0’s Inflection Point

Hannover-Messe 2019 and the Slovakian Engineer’s Joke: Industry 4.0’s Inflection Point

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Brad Canham

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Why is the hype about the adoption of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) different this time? What is a Slovakian engineer’s joke-telling us about an inflection point in the adoption of wireless in manufacturing? The joke told by a Slovakian engineer at Hannover-Messe 2019 “struck” a cord. It's the short version of why, this time, even if this IIoT inflection point is a bubble, it’s still the beginning of a “hockey stick”:

“There was a global study of nations noting each country's percentage of fiber to the home connectivity. South Korea had 30% of homes with fiber. North Korea had 0% homes with fiber connectivity. Germany had 7% fiber in the home. Germany’s technical modernization is closer to North Korea than it is to South Korea!"

Image Credit: LiveFish

What was witnessed at Hannover-Messe 2019 was this: previously conservative manufacturing groups, like those in Germany, leaped forward in acceptance of wireless IIoT. IIoT is at an inflection point. Explaining the reasons why—and why enterprise Bluetooth networks emerged strongly—takes a bit longer.

Previously conservative manufacturing groups, like those in Germany, have leaped forward in acceptance of wireless IIoT. Industry 4.0 is penetrating the infrastructure of businesses and governments.

In Industry 4.0, the Speed of Speed Is Faster

Image Credit: Brad Canham

First, let’s be clear. There are a lot of characteristics of IIoT and Industry 4.0 that are “bubbly.” In fact, even the language of the space is bubbly. Notably, there is no common, widespread definition for the term “Industry 4.0." The current terms and language used to describe Industry 4.0 draw largely from previous industrial eras. (Today’s definitions are a lot like describing “surfing the World Wide Web” to your grandmother in 1985.)

Further, the Industry 4.0 characteristics emphasize difficult-to-describe organizational characteristics, such as decentralization, complexity, exponential growth, speed, unpredictability, and change. As punctuation to this definitional indeterminacy, IoT, a key Industry 4.0 technology, has not yet been consistently defined in academic literature.

Notably, one clear characteristic of Industry 4.0 that distinguishes it from previous eras is how fast it is penetrating the infrastructure of businesses and governments. As the Slovakian engineer noted, German manufacturing is “waking up” to a worldwide manufacturing environment that is moving faster and in seemingly chaotic ways. As a variation on James Carville phrase, coined for Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, “It’s the era, stupid.”

IoT Isn’t Crossing the Chasm …It’s Navigating the Stream

In fact, for many IoT companies, the worn-smooth linear process of “crossing the chasm” is instead a permanent chasm “freefall” into a chaotically liquid landscape of technological and social shifts. As Cisco’s survey (2017) noted of the three-fourth failure rate of IoT projects, IoT companies are not easily moving from point A, early adopter, to point B, early majority, in the IoT chasm-crossing world. IoT companies can’t avoid bubbles because they happen quickly, form around your organization, pop, and reform constantly. In IoT, technical and social change happens so continually and quickly (e.g., Bluetooth 5.1 locationing within centimeters California Consumer Privacy Act), crossing a so-called chasm at the same speed of the IoT marketplace ceases to mean anything.

Welcome to the Quantum Marketplace

As they say in Buddhism, there is no sacred text. While Crossing the Chasm is a helpful guide for getting to the market stream, so to speak, it is increasingly less helpful for navigating the social and technological characteristics of IoT, such as unprecedented speed, fuzzy definitions, the Agile blurring of technology/ethics/people, etc. IoT is, in effect, flooding the technology adoption lifecycle and landscape with observer effects, fast-moving anomalies, black swans, and deep-in-the-swamp dilemmas.

Aligning material and social realities and goals with emergent phenomena is an unsettling experience. Emergent phenomena—and ultimately the new paradigm they support—challenge the status quo in new and disturbing ways. Also, emergent phenomena in a new era, like Industry 4.0, don't move in a linear fashion. They spider throughout a system erratically and in sudden bursts, socially and technically. For example, Bluetooth expert Sandeep Kamath of Swaralink Technologies noted, “Phones drive what people think the Bluetooth standard is…but with long-range Bluetooth 5.0 standard, the conversation is changing.” Is it possible that people’s attitudes about their phone technology are driving IIoT technology adoption? The Slovakian engineer’s joke reflects underlying anxiety that German manufacturing isn't positioned to leverage its strengths at an inflection point as emergent phenomena create a new paradigm.

Karl Marx and Industry 4.0: Material Meets Social

Image Credit: Brad Canham

Way back in the era of the First Industrial Revolution, Marx stressed that the “social and material” components of an era are a duality. In other words, they are inseparable. Industry 4.0 is no different. In fact, a new line of research called “sociomateriality” is based on the dissolving of boundaries between technology (the material) and people (the social).

When the term “Industry 4.0” was first coined at the 2011 Hannover-Messe Fair, many nations jumped on it and started developing interconnected industrial systems and processes. By contrast, while the automobile industry in Germany is on the leading edge of Industry 4.0, many other German industries took more of a wait-and-see approach. As a leader in Europe, Germany sets the pace of new technology adoption by many of its neighbors and the world.

Up until late 2017, many factories were over capacity and production demands were strong. Moreover, part of the social fabric of Germany industry involves decisions made as part of social network think tanks involving German industry, government, and academic partners. New material (i.e., technologies) is vetted and gets a stamp of approval via these informal and formal networks. Without the stamp, so to speak, German factories are slower to move forward on new technologies. In late 2017, production demand was high and profits were flowing, so as for new-fangled IoT technologies …eh, maybe next year. Well, next year arrived in 2019.

Why the Change? The Social Material of Industry 4.0 Technology

Image Credit: Brad Canham

As identified by a McKinsey report, Industry 4.0 is not merely a collection of the top 12 “technologies that matter,” such as IoT, big data, artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and others. By total revenue impact, IoT is the largest of these 12 new technologies. Industry 4.0 is also broadly composed of social realities, such as privacy, security, trade unions, politics, etc., as well as emergent countervailing forces and critics of the new Industry 4.0 characteristics, such as expressed in the General Data Practice Regulations (GDPR) and concerns about surveillance capitalism.

Trade unions in Europe are expressing skepticism about asset-tracking technologies that secondarily track workers associated with those assets. And don’t forget the new “social norms,” such as being polite about not capturing people doing odd things in the background when you take a selfie in a public place. In fact, there are researchers who primarily describe Industry 4.0 as a combination of social and technical factors working together in “trust clusters.”

In this case, Germany’s fundamentally conservative networks for adoption of Industry 4.0 at Hannover-Messe 2018 had a vibe along the lines of, “Hey, we got this. High-quality is synonymous with German engineering for a reason.” In 2019, the acceptance of the “interconnection” design principle of Industry 4.0 leaped ahead in a nonlinear surge, moving forward several years, in just 12 months, beyond the 2018 consensus. The question is, “Why?”

Complex Adaptive Systems: Nonlinearity Is the New Norm

Image Credit: Brad Canham

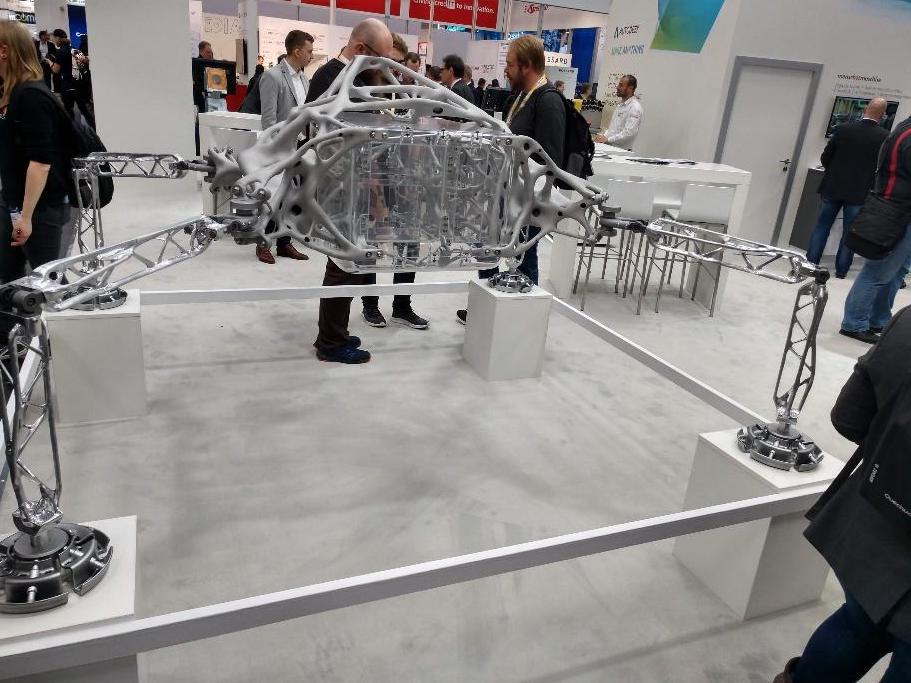

Firstly, Industry 4.0 has the characteristics of a complex adaptive system, where the combined independent activity of agents results in new structures and patterns arising in a system. The surge in acceptance of wireless connectivity, particularly enterprise Bluetooth networking employing predictive maintenance capabilities, emerged strongly at Hannover-Messe in 2019, with leading predictive maintenance companies like ABB embracing it.

The Springtime of Wireless in IIoT

Image Credit: Brad Canham

“Strong emergence” is characteristic of a system shift where a nonlinear change moves forward to a new level of order, conferring “additional capacity” in terms of outcomes. In other words, springtime! The new level of order as a major shift in the entire system is a non-proportional response to inputs. Tracing the many inputs is difficult, but occasionally, a single word, action, or even a joke can initiate a major shift in an entire system.

Factors of a Shift Writ Large and Small

The Slovakian engineer’s joke is a great short-version explainer. But, for those with a more quantitative-oriented viewpoint, here are a few macroeconomic data points to consider.

Growth projections for German manufacturing plunged throughout 2018 and into 2019 (Bloomberg, April 4, 2019). The downturn in growth increased competition between manufacturing firms. As a result, firms are likely more accepting of Industry 4.0 data projects, like predictive maintenance, to successfully compete.

Further, as a German academic researcher into industry 4.0 at Hannover-Messe 2019 noted, German companies can be a “little bit lazy” with adding new technologies. Many manufacturers have retrofitted existing machines to a high-quality peak. There, they hoped to ride profits as long as possible. However, when additional quality improvements are needed beyond retrofitting to compete, data-derived wireless quality insights, rather than expensive wired sensors or retrofits, are a more cost-effective step. As noted by the researcher “Predictive maintenance is the first point for this wireless data.”

Slumps Are Good for the Growth of Optimizers

Speaking of growth slumps, global economic growth is the lowest since 2008 (Bloomberg, April 9). Macroeconomic factors like Brexit and the unstable trade situation between the U.S. and China are good news for solutions enabling low-cost data gathering capabilities, which in turn allow manufacturing companies to optimize, achieving more with less. Takeaway? Production quality optimizers using low-cost wireless data are winners in a slowing economy.

Further, microeconomic attitudes (aka, talk on the street) also reflect the danger of Germany’s slow status quo approach to Industry 4.0 technology adoption. According to one engineer, there are German manufacturers who continue to build what they’ve built for the past 50 years, even though they're no longer directly selling their products on the market.

Tidbits, like the one above, aren’t a thorough basis for an analysis of wide claims, but they do provide intuitive market analysis, informing strategic decisions about product positioning in the dynamic space of IoT. Combining the macroeconomic data with microeconomic attitudes, a sense of “Why wireless?” surged. Adding the following use-case models and market factors further fills in the picture.

Market Factors of a Wireless Emergence in Industry 4.0

The cost of wiring in factories is high. Manufacturers are increasingly looking for wireless alternatives to conducting monitoring and predictive maintenance.

- Wire costs vary by industry, but some are very expensive. For example, in the metallurgy industry, running a wired connection to a sensor can cost up to 1000 Euros per meter.

- New wires are almost always a custom project in factories involving costly engineering and certification processes.

- Very small factories simply run wires whenever and wherever they want, but mid-size and large factories can’t do that and are looking at wireless.

- Testbeds in factories involve 6+ sensors per testbed. Wireless sensors ease space and cost issues.

- Over-burdened compliance inspectors in Italy and Germany are interested in offering predictive maintenance wireless systems to ensure compliance. There aren’t enough compliance inspectors or funds for adding more, so they only review a factory yearly or less.

- Many manufacturers investigating wireless over wired for the first time note the low cost, ease of install, and ease of use of wireless systems. This puts price pressures on wired monitoring providers. Some solutions are to employ hybrid wired and wireless options. Other innovative responses by smart wire manufacturers, like Minnesota Wire, include putting new sensor tech in custom or existing wire.

- There are many layers in the wiring costs beyond the cost of the wires themselves. Labor costs are typically one-third to one-half the cost.

- Running wired sensors to new machine retrofits can cost several times the cost of the retrofit. Faced with high wired costs, manufacturers are increasingly reviewing wireless options for sensors on new retrofits.

As the IoT World Turns…on a Slovakian Engineer’s Joke

At the moment, the IIoT inflection point for the adoption of wireless connectivity has been based on macroeconomic forces, qualitative market factors, interviews from an industry-defining event, a Slovakian engineer’s joke, and a small fish. At some point soon, an industry expert will turn to the nearly 30-year-old crossing-the-chasm model, or some variation of it, and declare they saw it coming.

Business models get old, but jokes last forever. The Slovakian engineer’s joke struck me. It was the inflection point, because, It’s the era, stupid.

Image Credit: YouTube

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

Monetizing Connected Cars

Related Articles