You’re Being Sold on the Internet

You’re Being Sold on the Internet

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

Yitaek Hwang

- Last Updated: December 2, 2024

You’ve already read about the big data breaches at the DNC, retail stores, and even tech companies. Yet most people brush it off as if this is just a script for an episode of Mr. Robot or Black Mirror. The scary part is that it’s not. Someone on the Internet is stealing your identity right now, from health records to internet browsing history to credit card information.

We’ve focused quite a bit on security in the past few weeks (see Calum McClelland’s “ IoT Security - Why We Need to be Securing the Internet of Things” series or my summary of “Google’s Infrastructure Security Design Overview”), and we continue with that theme this week.

James Scott, a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology, published a lengthy report on data brokers, next-gen hybrid information warfare, and the terrifying future of our privacy. You can read the original 56-page report or read our key takeaways below.

Information is Power

For years, the brightest minds in Silicon Valley have been accumulating information from consumers to get them to click on ads. Unfortunately, this effort was not regulated at all. Consumers gave up all their privacy and allowed companies to collect all sorts of data, who banked on its potential value for predicting behavior.

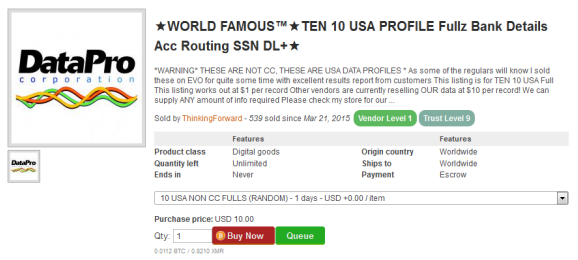

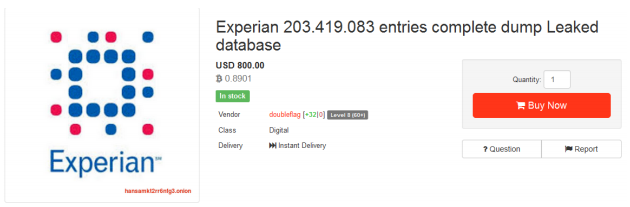

As big data analytics and machine learning algorithms continued to advance, organizations who collected data and data brokers who resold that data profited immensely, while largely neglecting to protect the privacy of those individuals. Anyone wishing to buy data can gain access to one’s credit card information, health records, online purchase history, GPS information, and more on the deep web.

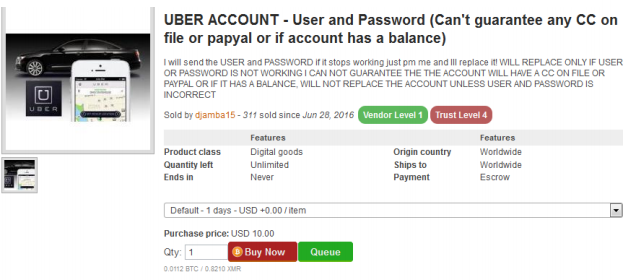

The worst part is that consumers often don’t know what privacy rights they are waiving and don’t know when someone buys their personal information online. For example, if you ever signed up for Uber, there is a chance that someone has your hacked username and password.

Next-Generation of Hybrid Information Warfare

The author of the report goes on to highlight the potential of hackers using this information to target critical infrastructure and high-level figures. If someone with access to all this data has malicious intent, he or she could theoretically wage “information warfare attacks that leverage demographic and psychographic algorithm insights.” Just from the Uber account alone, a hacker may find out travel logs of key personnel and stage an attack using that information.

James Scott goes on to say that America lags behind global privacy initiatives. Consumers rarely take time to read the tedious “Terms and Conditions” and data brokers don’t have defined guidelines for data collection and protection. This is in stark contrast to those of the European Union, which has Fair Information Practices written into regulatory standards and laws.

Who are these Data Brokers?

Data brokers collect information from a wide range of streams: government records, tax records, driver’s license, voter registration, census data, survey entries, social media, web browsing activity, email, healthcare forms, and even recreational licenses. The FTC groups data brokers into three categories:

- Marketing Products: Perhaps the most well-known, these brokers collect marketing information and analytics to predict consumer behavior.

- Risk Mitigation: These brokers sell fraud detection products to banks, government agencies, and others to confirm the identity of individuals.

- People Search: As the name suggests, data brokers of this type sell select fields of personal information about people to individual consumers, law enforcement, private investigators, and the media.

Despite the tremendous amount of data that these brokers have, the FTC only enforces data protection measures if the information is used for credit, employment, insurance, or housing purposes. Stronger measures have been proposed in the past (e.g. Data Security and Breach Notification Act to require data brokers to inform consumers of breached data), but all have been killed off by Congress since 2009.

Problems

- Little Consumer Protection: Most rational consumers understand that they provide some of their demographic and behavioral data in exchange for some service (e.g. search engine, social media, games). However, consumers don’t know how their data is being monetized or who purchases that data.

- Data Brokers are Negligent: Data brokers take little measures to encrypt, protect, and track data being breached or sold. It’s easy for cyberattackers to steal this information or even cross-reference multiple databases to crack hasty encryption protocols.

- Malicious Attacks: Given how easy it is for cyber-adversaries to either steal or buy insufficiently anonymized data, precision targeted attacks on critical infrastructure executives and organizations aren’t hard to imagine. The report details examples of attacks from China.

Conclusion

The report ends with a summary of how our data is at risk of being stolen and leveraged against us in a new age of information warfare. The author uses an alarmist tone to warn that both the average consumer and American key personnel are “just a victimization case waiting for an adversary.”

While no recommended steps are listed, I hope this spurs a productive dialogue about the need for stronger protection measures on a national level.

The Most Comprehensive IoT Newsletter for Enterprises

Showcasing the highest-quality content, resources, news, and insights from the world of the Internet of Things. Subscribe to remain informed and up-to-date.

New Podcast Episode

What is Software-Defined Connectivity?

Related Articles